This article has been prompted by the dismissal of a rail employee for failing to follow a standard operating procedure, resulting in a significant derailment. The key questions here are:

- How likely is this to reduce the likelihood of similar, future events?

- What impact is this likely to have on the identification of future opportunities for reliability and safety improvement?

These should be the intent of any incident investigation, and this article will argue that dismissing the employee, in the absence of any other improvement actions, will, at best, most likely have no sustainable effect on achieving these objectives and, at worst, will inhibit future safety and reliability improvement initiatives.

I should point out that I am not privy to the specific details of the incident that prompted this article, and there may be exceptional circumstances relating to this specific incident which merit the punishment meted out, but as a general rule, we need to be very careful in using punishment as our first and primary response to any safety or reliability incident.

Who can we blame?

It seems to be a common human reaction to any major adverse event that one of the first, emotional responses is to try to find someone that we can hold responsible for that event, and then punish them. This is particularly the case when we have a strong emotional response to the event – especially if it makes us angry. However, research has shown that punishment of adults does not always bring about sustainable behavioural change – especially amongst other who were not directly associated with the event but who may be displaying similar behaviours. Sometimes it only temporarily stops one bad behaviour from occurring, but may also lead to fear, psychological tension, anxiety and other undesirable impacts. This, in turn, can have an adverse effect on productivity and future work behaviours.

Failure investigation and safety investigations are problem-solving processes

When we investigate a safety or reliability incident, we should treat this as being a problem-solving process. Our objective is to identify the solution(s) that we should put in place that reduces the risk of similar, future events occurring to As Low As Reasonably Practical (ALARP) or So Far As Is Reasonably Practical (SFAIRP) (the choice depending on your regulatory regime). Typically, a structured approach is taken, with the key steps being:

- Define the problem to be solved

- Collect evidence/data

- Identify incident causes

- Analyse incident causes

- Identify and select solutions

- Implement solutions

Our approach to failure investigation has 10 steps, rather than the six listed above, but for the sake of simplicity, we won’t go into this here. When it comes to identifying and analysing causes, we have found that regardless of the simplicity or complexity of the event or issue being investigated, there are always many contributing causes to that event.

Humans as a cause of failure

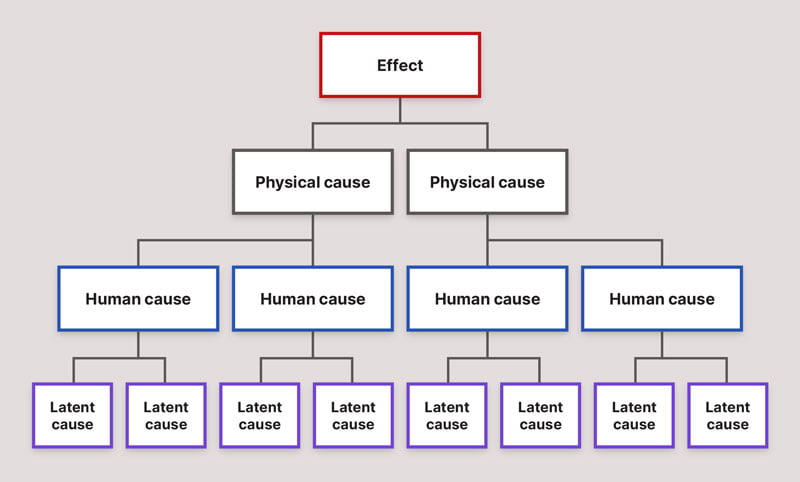

Latino and Latino (1) consider that causes of problems can be divided into three categories:

- Physical Causes are the tangible causes of failures – “the bearing seized”, for example.

- Human Causes almost always trigger a physical cause of failure – these could be errors of commission (we did something we shouldn’t do) or omission (we didn’t do something we should have done) – “the bearing was not properly lubricated” would be an example of a human cause.

- Latent Causes (or Organisational Causes) are the organisational systems that people used to make their decisions – “there is no system in place to ensure that the lubricator’s duties are performed when he is on annual leave”, for example.

We frequently find that these can be considered as a hierarchy of causes, with the most obvious causes being the physical causes. These are then most often generated by Human Causes (someone did something they shouldn’t have or didn’t do something they should have), which in turn are often the product of the situation or circumstances which they are in (the Latent Causes).

Latino and Latino argue persuasively that the most effective, sustainable solutions are those that address the Latent Causes of problems.

In order to successfully identify and address the underlying latent causes of failures, it is necessary, usually, to identify the errors of omission or commission that were committed by individuals, which led to the ensuing failure. This can be a daunting, and event terrifying experience for those who committed the errors. This terror can be compounded even further if there is a reluctance or inability to progress beyond the Human causes of failures and identify the Organisational causes, as it leaves “human error”, with all of its negative connotations for the person committing the error, as being the “root” cause of the failure. Very quickly, in this environment, it is easy to slip into the “blame game”. Investigations acquire a reputation as being a way of seeking and reprimanding individuals who “caused” the failure, and, not unsurprisingly, people then either refuse to participate, or refuse to provide sufficient, accurate information in order to prevent recurrence of the problem.

Allocating blame is counter-productive

Many organisations are quick to allocate blame for failures, and then seek to prevent recurrence either through disciplinary or “retraining” actions. However, in the vast majority of situations this is either ineffective, or even counter-productive. Our current beliefs regarding human error are generally that:

- Human error is infrequent

- Human error is intrinsically bad

- A few people are responsible for most of the human errors, and

- The most effective way of preventing human error is through disciplinary actions

On the other hand, most behavioural psychologists – among them Reason and Hobbs (2) – are now showing, through quantitative research, that:

Human error is inevitable.

Reason and Hobbs identified a number of physiological and psychological factors which contribute to the inevitability of human error, these include:

- Differences between the capabilities of our long-term memory and our conscious workspace

- The “Vigilance Decrement” – it is more common for inspectors to miss obvious faults the longer that they have been performing the inspection

- The impact of fatigue

- The level of arousal – too much or too little arousal impairs work performance, and

- Biases in thinking and decision making, as discussed earlier in this article

Human error is not intrinsically bad.

Success and failure spring from the same roots. Our desire to experiment and try new things (and learn from our mistakes) is the primary reason that the human race has progressed to its current stage of development. Fundamentally, we are error-guided creatures, and errors mark the boundaries of the path to successful action

Everybody commits errors.

No one is immune to error – if only a few people were responsible for most of the errors, then the solution would be simple, but some of the worst mistakes are made by the most experienced people.

Blame and punishment is almost always inappropriate.

People cannot easily avoid those actions they did not intend to commit. Blame and punishment is not appropriate when peoples’ intentions were good, but their actions did not go as planned. This does not mean, however, that people should not be accountable for their actions, and be given the opportunity to learn from their mistakes.

A better approach: establish a “no-blame” culture

Reason and Hobbs reinforce the view that, in their words “You cannot change the human condition, but you can change the conditions in which humans work” – in other words, address the underlying Latent Causes that led to the error being committed. They argue that successfully eliminating the natural fears that people have about being “blamed” for having made a mistake requires the proactive establishment of an organisational culture that has three components (3):

- A Just Culture – one in which there is agreement and understanding regarding the distinction between blame-free and culpable acts. Some actions undertaken by individuals will still warrant disciplinary action. They will be few in number, but cannot be ignored.

- A Reporting Culture – one which proactively seeks to overcome people’s natural tendencies not to admit their own mistakes, their suspicions that reporting their errors may count against them in future, and their scepticism that any improvements will result from reporting the error. This can be achieved a number of ways, such as by de-identifying individuals in reports, guaranteeing protection from disciplinary action, providing feedback and so on.

- A Learning Culture – one in which both reactive and proactive activities are performed in order to prevent future errors and failures.

Many organisations are littered with recommendations from Safety Investigations that are never implemented, simply because there is not the management will, or the management processes to deal with these. There is a tendency on the part of senior managers to assume that, when dealing with isolated events, the organisational causes that led to that event occurring are unusual or exceptional – and therefore there is no need to tinker with the underlying organisational processes, beliefs or systems that led to these unfortunate consequences. In other words, most managers see what they want to see, and ignore any “evidence” that does not correlate with their own view of the world. There are numerous examples of catastrophic failures that have occurred as a result of this selective blindness on the part of senior management personnel. The explosion at Esso Longford is one, such example. The loss of both the Columbia and Challenger space shuttles are two more. So-called “High Reliability Organisations” on the other hand, show a preoccupation with failure (4). They constantly encourage the reporting of errors, and treat any failure, no matter how small, as a symptom that something is wrong with their system – something that could eventually have catastrophic consequences if sufficient of these “small” failures happen to coincide at one point in time. This preoccupation with error, and the continual focus on refining processes and systems in order to eliminate error, is something that needs to be promoted and encouraged at all levels in the organisation, starting from the very top. But it can only happen if the organisational culture supports open and honest reporting of failures without fear of the consequences.

Civil Aviation is the safest and most reliable form of transport today – but it did not always have that reputation. Over the last 50 years it has continuously worked to eliminate failures. And it has done this in an open and transparent way that has no equivalent in any other industry. All significant aviation incidents are independently investigated. The results of the investigations are available to all airlines and the general public. And one of the most notable features of these investigations is that even when it is clear that an individual has made a mistake that contributed to (and in some cases was the major cause of) an accident, these investigations almost never recommend disciplinary action against the individual involved. Instead, the underlying philosophy is that human error is universal and inevitable; if we want to reduce failure risks then we need to make the systems within which people work more resilient to these errors.

Conclusion

I hope that this article helps to spark some debate within your organisation. If you would like help to establish more effective problem-solving and Root Cause Analysis processes and culture within your organisation, please feel free to contact me. I will be glad to help.

References

- R J Latino and K C Latino, “Root Cause Analysis – Improving Performance for Bottom Line Results”, CRC Press, pp 87-88 (1999)

- J Reason and A Hobbs, “Managing Maintenance Error”, Ashgate Publishing, pp 96 – 97 (2003)

- J Reason and A Hobbs, “Managing Maintenance Error”, Ashgate Publishing, pp 146 – 158 (2003)

- K Weick and K Sutcliffe, “Managing the Unexpected”, Jossey-Bass, pp 10 -11 (2001)