Times are tough. Your company isn’t making as much profit as it used to. Perhaps it isn’t making a profit at all. You need to cut costs, but where?

What about maintenance? Maintenance costs a lot of money, and in a slowing market, maybe you don’t need the equipment to be as reliable as we used to. Maybe you can defer maintenance till another time, when your finances look better. And in a budget that big, there is bound to be some fat that can be cut.

That may be true, but before you rush in and cut the maintenance budget, here are a few questions you should ask your Maintenance Manager (and the risks if you don’t).

What is the total cost of unreliability?

Unreliable equipment is often a source of considerable additional cost, regardless of market conditions. It is important to understand it, in order to make sure that you are targeting the right areas for cost reduction. The total cost of unreliability is made up of several elements:

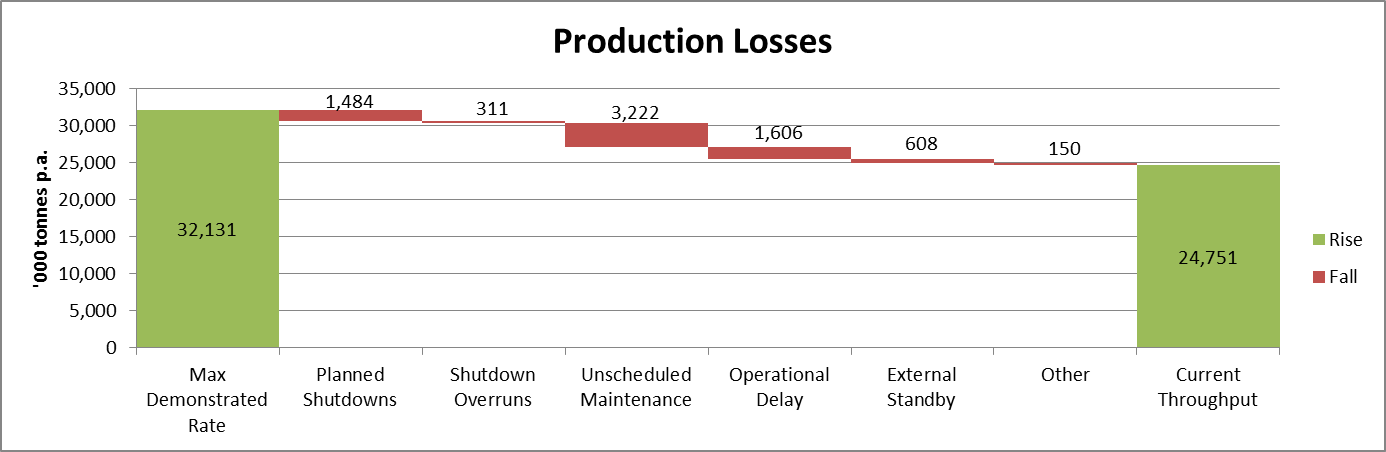

- The lost contribution to profit that results from equipment not being available to produce at full rates. This is, essentially, the difference between the lost sales revenue and the variable cost of production. Assuming that you can sell all that you can make (for example if you are in the mining, oil & gas, or other commodity market), then this can be considerable – especially if your fixed costs are high, as they typically are in those industries, due to the large investment in fixed assets required to build operating plants. We can illustrate the production losses and their high level causes in a waterfall chart, similar to the one shown above, and this can help to focus attention on the areas of greatest opportunity. Converting the production losses into revenue or profit losses can also assist in identifying the potential size of the prize that is on offer. For the organisation illustrated above, the initial focus of attention was on reducing planned shutdown overruns – but you can see that the potential gains achievable from this source are less than 1/10th of the potential gains by reducing breakdowns and unscheduled maintenance.

- Additional operating costs associated with having to achieve target production levels. These could include the costs of having to man additional operating shifts, or pay operators overtime (if you do not already operate 24×7) to meet production costs, or the opportunity lost to reduce operating shifts, if the equipment were operating reliably. Plus the additional supervision required, the additional costs with keeping the factory lit and heated or cooled etc etc. In some cases, you may need to contract out some production operations in order to meet production targets, and this can also be a significant cost.

- Additional maintenance costs associated with the higher level of breakdowns. We will touch on this in more detail in a later point.

- Additional costs or lost revenue associated with poor product quality. Frequently, when equipment fails, it leads to some product failing to meet the required quality standards – or alternatively, when attempting to “catch up” lost production, quality standards are sometimes slackened. If this leads to having to rework or reprocess sub-standard product, or having to discount the sales price for product in order for customers to accept it, then the cost of this reprocessing, or the revenue lost should also be considered.

- The costs of poorer safety performance, and higher numbers of environmental incidents. While it is possible to target your budget cuts so as not to impact on safety-critical or environmental-critical equipment, all maintenance work carries some safety and environmental risks, regardless of the equipment being worked on, and this is even higher when this work is being performed in a high-pressure, equipment breakdown situation. A number of studies have shown a high level of correlation between plant reliability and safety – a reliable plant is a safe plant. It is a brave manager that ignores these statistics, and potentially puts their workforce at higher risk through acceptance of lower equipment reliability.

There is a temptation to believe that, because the market is soft, and your production targets are lower, that there is a sound business case for spending less on maintenance, and allowing equipment to be less reliable. This may or may not be the case. You need to understand the true total cost of equipment unreliability before making that call. Otherwise, you may find that maintenance costs and operating costs end up being higher than you thought, and you may struggle to meet your planned production targets. Leading organisations tend to treat a goal of high reliability as being non-negotiable, much the same as their goals for safety. And this tends to become a virtuous circle – the higher the level of plant reliability, then the lower the unit cost of production and the safer the plant – allowing more time to be “ahead of the game” and working towards the next level of reliability improvement.

How much maintenance work is truly discretionary?

Broadly speaking, Maintenance work is made up of four different categories of work:

- Preventive Maintenance – those routine inspections, overhauls, services and tests which are carried out in order to either prevent equipment from failing, or to detect whether it is about to fail, so that repairs can be scheduled before it does.

- Corrective Maintenance – planned repairs that are carried out (often as a result of a Preventive Maintenance inspection) to repair equipment before it fails, or in some cases (for non-critical equipment where no Preventive Maintenance strategy is in place), to repair it after it has failed.

- Breakdown and/or Break-in Maintenance – unplanned repairs that are carried out in an urgent response to equipment that has either failed or is in imminent danger of failing.

- Equipment Modifications – strictly speaking this work is not “maintenance”, as it is not intended to restore equipment to its original condition, but at many organisations, the maintenance workforce are involved in performing these modifications.

So how much of this work can be reduced or eliminated?

In the short term, Breakdown and Break-in work must be done. While in the longer run, eliminating those failures altogether is a desirable goal (and should be a priority), in the short term, not fixing broken down equipment is not an option – unless you don’t need the equipment at all, in which case, you would have to ask why you were operating it. So this must be funded.

Similarly, Corrective Maintenance must be done at some point in time. While some of this work may be able to be deferred, at some point the equipment must be repaired if the equipment is needed. Of course, there are risks associated with deferring Corrective Maintenance. Primary amongst those is the risk that equipment which has not yet failed (but which is known is about to fail) may fail catastrophically before the appropriate corrective maintenance is done. Depending on the equipment, this may have a significant impact on total plant costs (see the previous point “What is the cost of unreliability?”) as well as increasing the direct cost of the repairs (see the later point “How much does it cost to repair equipment after it has broken, rather than prevent it from breaking in the first place?”). Understanding those risks is vital, before you squeeze the maintenance budget too hard. In addition, Corrective Maintenance can only be deferred for a finite length of time – it does need to be done at some point. This can have the effect of pushing a “bow wave” of maintenance expenditure into future time periods. You need to understand that the need for the maintenance work doesn’t go away – it needs to be budgeted for in those future time periods. Failing to do that can give the mistaken impression that maintenance costs have been permanently reduced, not just deferred. In some cases, corrective maintenance activities can be deferred for years with minimal impact on equipment performance in the short term, but significant impact on maintenance costs and/or equipment performance in the medium to longer term. Do you and your Maintenance Manager fully understand all of the implications of deferring Corrective Maintenance?

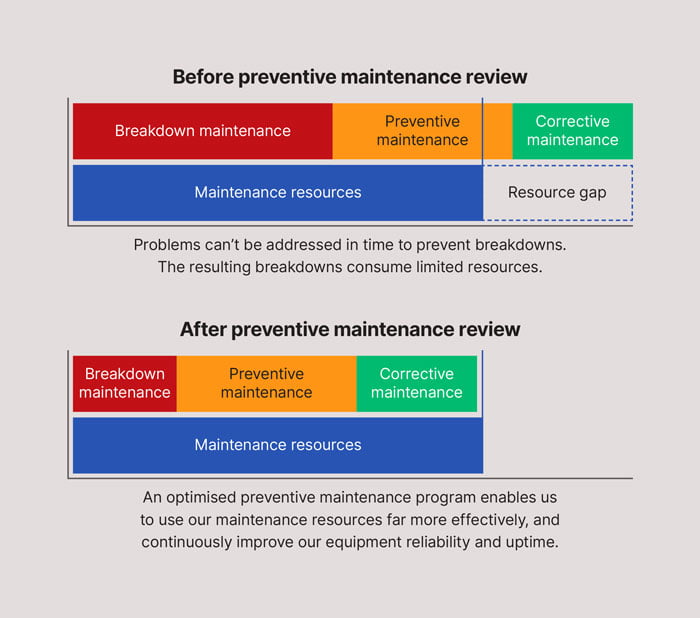

There can be a temptation, particularly in a soft market, to believe that you can reduce the amount of Preventive Maintenance work that is done. This may be true, but the selection of which Preventive Maintenance work can be eliminated or reduced in scope needs to be done intelligently (see the later point “Is the Preventive Maintenance program optimised for current operations?”). Indiscriminately, or inappropriately reducing the frequency of performing Preventive Maintenance tasks (including plant shutdowns), or eliminating Preventive Maintenance tasks altogether can have a seriously detrimental effect on overall plant reliability and performance. There is a risk that incipient failures go undetected, resulting in a higher level of breakdown maintenance.

The only category of maintenance expenditure that is truly discretionary is the work performed to modify or improve equipment. In the short term, this can generally be significantly reduced or eliminated – but in the long run, this can be detrimental. If you are not improving your equipment performance, but your competitors are, then sooner or later you will fall behind.

If you simply reduce maintenance headcount, without understanding what maintenance work is no longer going to be done, then maintenance will perform the highest priority work first, and the lowest priority work will either not be done or will be deferred. In practice, this means that the first work that will be deferred is improvement work, closely followed by Corrective Maintenance and Preventive Maintenance work that is seen to be “lower priority”. Squeeze too hard, and this will result in an increased number of breakdowns.

What are the risks associated with deferring or not performing maintenance?

Insufficient spending on maintenance has been a significant contributor to a number of industrial accidents with serious safety, environmental and political consequences.

The explosion at Union Carbide’s Bhopal Pesticide Plant in India occurred largely as a result of under-maintenance of significant safety critical systems. The official immediate death toll was 2,259. A government affidavit in 2006 stated that the leak caused 558,125 injuries, including 38,478 temporary partial injuries and approximately 3,900 severely and permanently disabling injuries. In June 2010, seven ex-employees, including the former chairman, were convicted in Bhopal of causing death by negligence and sentenced to two years imprisonment.

The Piper Alpha explosion in the North Sea killed 167 men. The ensuing Cullen Inquiry resulted in Piper Alpha’s operator, Occidental, being found guilty of having inadequate maintenance and safety procedures – although criminal charges were never laid.

At Potters Bar in the UK, a train derailment killed 7 people and injured 76. A subsequent enquiry found that a set of points was poorly maintained and that this was the principal cause of the accident. Charges were laid under the Health and Safety at Work Act, and Network Rail was fined £3 million for safety failings related to the crash.

An explosion at the Varanus Island Gas Plant in Australia fortunately did not result in fatalities, but reduced Western Australia’s gas supply by around a third for almost two months. Many Western Australian businesses were forced to curtail or cease operations, resulting in workers being stood down or forced to take annual leave, and the incident created significant public and political ill-will. The explosion was caused by rupture of a corroded pipeline. Court proceedings against the plant operator at the time, Apache Energy, were withdrawn due to a technicality relating to Apache’s licence.

With industrial manslaughter legislation being progressively introduced across the world, do you understand the risks that you are taking when you cut the Maintenance Budget?

How much more does it cost to repair equipment after it has failed, compared with preventing it from failing?

Even if we believe that there are no significant safety or environmental risks associated with deferring or cancelling maintenance, there could be significant commercial implications. Intuitively, we understand that preventing equipment from failing is preferable to fixing it after it breaks. But do you and your Maintenance Manager understand how much more it costs to repair equipment after it fails?

Anecdotally, statements are made that say things like “Breakdown Maintenance costs 6-9 times more than Preventive Maintenance”. However there is little or no empirical evidence to support these general statements and it is not clear what costs are included in this analysis.

The truth of the matter is that the true additional cost of fixing equipment after it fails compared with the costs if you prevent it from failing depends on a number of factors. Some of these include:

- The financial implications of the failed equipment not operating while the breakdown repairs are completed

- The extent of consequential damage to the failed equipment or associated equipment that may result from the failure

- Whether all of the spare parts required to perform the repairs readily available?

- Whether there is sufficient, skilled labour available at short notice to perform the repairs?

- Whether there is an opportunity to perform additional preventive or corrective work on other equipment when the failed equipment is out of service, that otherwise would have required a planned shutdown?

It is clear that for some failures (particularly on critical equipment) the additional costs of performing breakdown work, rather than preventive or planned work, can be substantial. Do you and your maintenance manager understand what these high-risk failures are, and which equipment is likely to be affected? If you do not, then there is a risk that maintenance expenditure and preventive maintenance activities will be cut on the wrong equipment, and that you may incur some unpleasant budgetary surprises if this equipment fails.

Do you understand what is causing equipment unreliability, and what is being done to eliminate these causes?

As we saw earlier, when maintenance resources are scarce, lower priority work will end up being deferred. Squeeze the maintenance budget too hard and it means that will be fewer maintenance resources available to work on eliminating the causes of breakdowns. Leading organisations have, for decades, shown that the only sustainable way to reduce maintenance costs in the long run is to progressively improve plant and equipment reliability by eliminating the causes of equipment failure. Too do this, you need to effectively analyse those failures to understand their causes. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that you need to spend lots of money upgrading equipment. A large number of failures can be eliminated by focusing on the underlying latent or organisational causes, such as:

- Inappropriate operating procedures

- Inadequate operating discipline

- Poor installation and commissioning procedures

- Inappropriate or inadequate preventive maintenance strategies (more on this in the next point)

- Inadequate repair specifications and procedures

- Inadequately skilled operators or maintainers

- Inadequately specified spare parts

- Poor spare parts care

- Shortage of proper tooling and support equipment

- Operator and Maintainer fatigue

But if you don’t know the extent to which these factors are contributing to poor equipment reliability, then you won’t know where to start. Ask your Maintenance Manager if he understands where the priorities lie in addressing these causes, and then make sure that there is adequate funding and resourcing to tackle these issues – otherwise it is highly likely that these failures will continue to happen, and suck up scarce maintenance resources and money in performing breakdown repairs, rather than breakdown prevention.

Where are the opportunities to improve maintenance workforce productivity?

So far we have mostly discussed opportunities to improve Maintenance Effectiveness – making sure maintenance funds are being spent on doing the right things. But where are the opportunities to improve Maintenance Productivity – get the same work done more efficiently?

The biggest lever that can be pulled here is to improve Maintenance “tool-time”, the amount of time that shopfloor maintenance personnel spend efficiently performing repairs and preventive maintenance activities. At many organisations, these people spend less than 50% of their time efficiently performing maintenance work – in some cases, significantly less than 50%. Does your Maintenance Manager know what proportion of time his maintenance workforce spends as “tool-time”?

The key to increasing tool-time is to reduce or eliminate those things that cause delays for your shopfloor Maintenance workers. This includes causes such as:

- Waiting for permits

- Waiting for equipment to be isolated and/or cleaned

- Waiting for or searching for the parts that are needed to do a job

- Waiting for support equipment or resources, such as cranes, scaffolding, special tools etc

- Waiting for instructions on what job to do, or how to do it

In our experience, almost all maintenance workers do not deliberately set out to cause these delays – they are victims of the systems within which they work which induce these delays. A focus on improving the quality and level of detail in Maintenance Planning and Scheduling will certainly help. But, making these improvements, changing these systems, and embedding the changes within the culture of the organisation will probably take time – typically measured in years, not months, for larger organisations. So in the meantime, reducing maintenance headcount, while superficially improving maintenance productivity, may not necessarily increase the amount of maintenance work being done by each maintenance worker – rather, it may simply lead to less maintenance work being done, with the risks inherent in that outcome (see the earlier point “How much Maintenance work is truly discretionary”). Ask your Maintenance Manager what he is doing to reduce the on-the-job delays being experienced by the Maintenance workforce?

Conclusion

Reducing the maintenance budget means that either:

- the same amount of maintenance work will need to be done more efficiently, or

- some maintenance work will have to be deferred, or

- some maintenance work will not be able to be done at all.

As we have discussed in this article, it is important that:

- you and your Maintenance Manager understand the limitations and risks associated with each of these three options,

- your Maintenance Manager selectively and logically targets those areas in which cost reductions can safely be made with the lowest level of associated risk, and that

- you and your Maintenance Manager agree on:

- the level of cost reduction that is achievable

- the specific changes to maintenance practices and strategies that are going to be implemented to achieve the target reduction in costs, and

- the short term and longer term changes to business risks that are associated with these changes in maintenance practices.

Simply reducing the maintenance budget without a clear understanding of what maintenance practices and strategies will need to be changed in order to achieve the target reduction in costs is a high risk strategy. At best, maintenance costs may not reduce at all, regardless of what is budgeted. At worst, maintenance costs may increase – both in the short term and the long term.

If you or your Maintenance Manager has difficulty answering any of the questions in this article, we can assist. Contact us today to discuss your situation and your needs.

For future useful articles sign up to our mailing list now.