We, as maintenance reliability professionals, are convinced of the benefits that improved maintenance and reliability practices can bring to an organisation. Often, we are passionate about our cause. But senior managers at many organisations are yet to share our passion and our faith in the value of Reliability Improvement. Why are they waiting? Why do they not share our enthusiasm and actively support us in our improvement efforts? To answer this question, we must look at how we are communicating our passion, and how we “package” our pitch for support.

Clearly, our proposal must resonate with key decision makers. There are two elements to making it resonate. It must resonate both:

- Rationally – it must appeal to their brains, and

- Emotionally – it must appeal to their hearts (and yes, Senior Managers do have hearts!)

Why do we need to appeal to both heads and hearts? There is an increasing body of evidence being generated by neuroscientists and psychologists that suggests that, in many cases, we make initial decisions very quickly, guided by our emotions, and then subsequently evaluate that decision using rational decision making criteria. But one of the pitfalls of our emotional brain is that it requires pretty powerful rational proof to overcome the initial, emotional decision that we made. So clearly your proposal must have strong elements of rational and emotional arguments in order to have any sort of impact on decision makers.

Let’s take a closer look at the two approaches and how you can apply these to selling your reliability improvement program to senior management.

Making your proposition resonate rationally

In order for your proposition to resonate rationally, there are a few critical elements to consider.

First, there must be a sound business case. The proposition must demonstrate real business value. This means that we need to be able to estimate and articulate the costs, benefits and risks associated with your proposition. This, in turn, means that we need to be able to talk in a language that senior managers understand – money.

So some of the things that we need to ask ourselves are questions such as:

- How much is 1% extra production output worth to my organisation?

- How much will reducing maintenance costs by 1% save (and will there be any increase in risks as a result)?

- What is the $ value to my organisation of improving product or service quality?

Unless we know the answers to these questions, then we will struggle to develop the required business case.

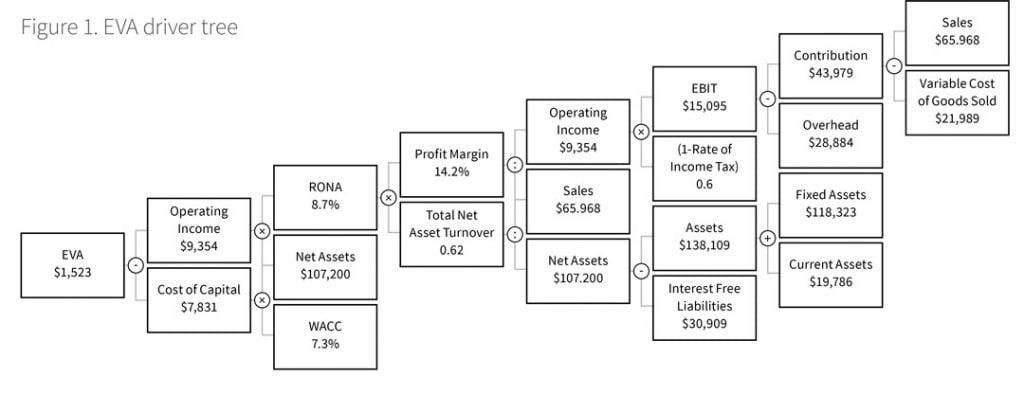

Second, we must be able to communicate our business case clearly and concisely. Senior managers don’t have a lot of time to wade through lots of technical detail – even if they understand it). One very useful tool for both communicating and visualising the value of improved reliability is the Economic Value Add (EVA) driver diagram. Describing how this works is beyond the scope of this blog post, but if you are interested, then you can read more on Wikipedia, or at the Obermatt website. Essentially EVA is the value created in excess of the required return of the company’s investors (i.e. their shareholders and those to whom they owe debt).

From this, we can see that reliability improvement can generate increased EVA in a number of different ways, such as by:

- Increasing equipment uptime and therefore company sales

- Reducing the direct costs of production (both operating and maintenance costs)

- Reducing the value of fixed assets that are required in order to produce a given (fixed) amount of production

- Reducing the amount of working capital that is tied up in spare parts

- Reducing overall business risks (and therefore reducing the Weighted Average Cost of Capital – WACC)

Furthermore, if we have the numbers at hand, we can quantify the impact of these improvements on overall EVA.

Bear in mind, however, that we will probably also need to demonstrate that our proposal meets the minimum hurdle values associated with whatever investment decision criteria are used within our organisation (e.g. Net Present Value, Internal Rate of Return, Payback Period etc.) – so we had better find out what those decision criteria are, and the associated hurdle values that need to be met for approval.

Making your proposition resonate emotionally

Providing the economic rationale for our proposal is necessary, but not sufficient. As human beings, our emotions affect every decision that we make – in many cases in ways that we are not even aware of. The evidence is that we tend to make initial decisions guided by our emotions, and then subsequently evaluate that decision using rational decision making criteria. If you haven’t yet read Daniel Kahneman’s excellent book “Thinking, Fast and Slow”, then I strongly recommend that you do so, as this provides much more detailed discussion of these, and other related, concepts and the science behind them.

One of the pitfalls of our emotional brain is that it requires pretty powerful rational proof to overcome the initial, emotional decision that we made. For this reason, it is important that we generate the right initial emotional response to our proposal. So how can we effectively swing the balance of emotions in our favour? What are some of the keys to successfully tapping into the emotional side of decision makers? Based on the excellent animation, which is, in turn based on a TED talk “The Science of Persuasion”, some of the key factors that influence others’ emotional responses to us are:

- Empathy – Put simply, empathy is the ability to identify and understand another person’s feelings, ideas and situation. Research suggests that people are more likely to be persuaded by people that they like, and having empathy and a genuine interest in others is a key part of being liked.

- Sincerity – When combined with empathy, sincerity leads to trust. You need to be able to demonstrate through your behaviours and actions that you are sincere, and therefore worthy of trust – that you genuinely have the other parties best interests at heart.

- Reciprocity – Reciprocity in social psychology refers to responding to a positive action with another positive action. In more general terms, it means that if someone does you a favour, then you are more likely to feel obligated to do them a favour in return. In practice, what this means is that if you wish to have someone look favourably at your proposal, then you should do something good for them before you ask. However, the good deed must be sincerely felt. Research also suggests that the good deed will have more impact if it is personalised and unexpected.

- Authority – In the context of effective persuasion, people tend to be persuaded more if the suggestion or recommendation comes from someone who is seen as both credible and authoritative in the subject. So the key to success here is to either ensure that you are seen as credible and authoritative by the key decision makers, or enlist the support of someone else who is. This person could be either internal or external to your organisation.

- Consistency – People like to make decisions that are consistent with their previous statements and behaviours. They are more likely, therefore, to support proposals that are consistent with the overall strategic direction of the organisation, the culture that exists within the organisation and any public pronouncements that they have made. One key way of making use of this tendency is by gaining agreement from senior management to a smaller, less risky project first. A pilot project, study or trial is more likely to be favourably viewed, and, if successful, it will be easier to gain commitment to a larger scale project.

One of the biggest emotional hurdles to be overcome is our emotional attitude to risk. While we tend to believe that we can assess and manage risk in a rational manner (through risk matrices, formal risk management protocols etc), in practice, the data that we use to assess risk is imperfect, and as a result, our assessment of risk tends to be heavily influenced by our emotional attitude to risk. It is almost universally true that our fear of loss tends to outweigh our desire for gain, and so one of the key activities that you will need to perform if you are to have your proposal accepted, is to identify the key risks that are associated with your proposal, and make sure that you have successfully addressed both the rational and emotional aspects of senior management’s likely responses to those risks, and can give management a sense of comfort that the level of risk is tolerable. One possible approach that may enhance your chances of success is by taking advantage of management’s fear of loss by pointing out what they may miss out on if they don’t accept your proposal (rather than just focusing on what they may gain). This may also assist in generating a sense of urgency around completing your project.

So there you have it – if you want to sell the value of reliability improvement to senior managers, you need to appeal to both their hearts AND their heads.